by Alma Santang

I am a firm believer that design has the power to create an impact. I am not talking huge, world-changing impact, just enough to spark a little fire in someone’s heart. On Good Taste vs. Good Design, reciting Crozier (1994), it mentioned that design is a lifestyle, something aesthetically pleasing or fashionable. I would argue that this definition does not capture what design is in today’s society. In recent years, the interest in design for social good or social change (later referred to as social design) has been growing within the design professions and the design education community, as mentioned in an essay titled Social Design: From Utopia to the Good Society by Victor Margolin. Design has a bigger purpose than to entertain humankind, designers are now finding ways to contribute to society.

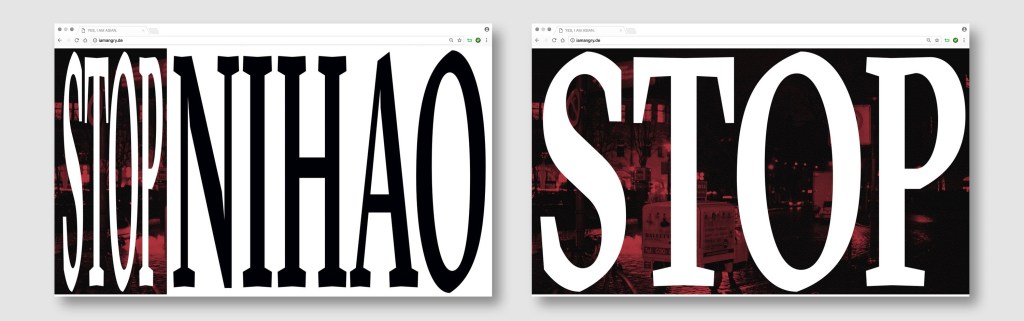

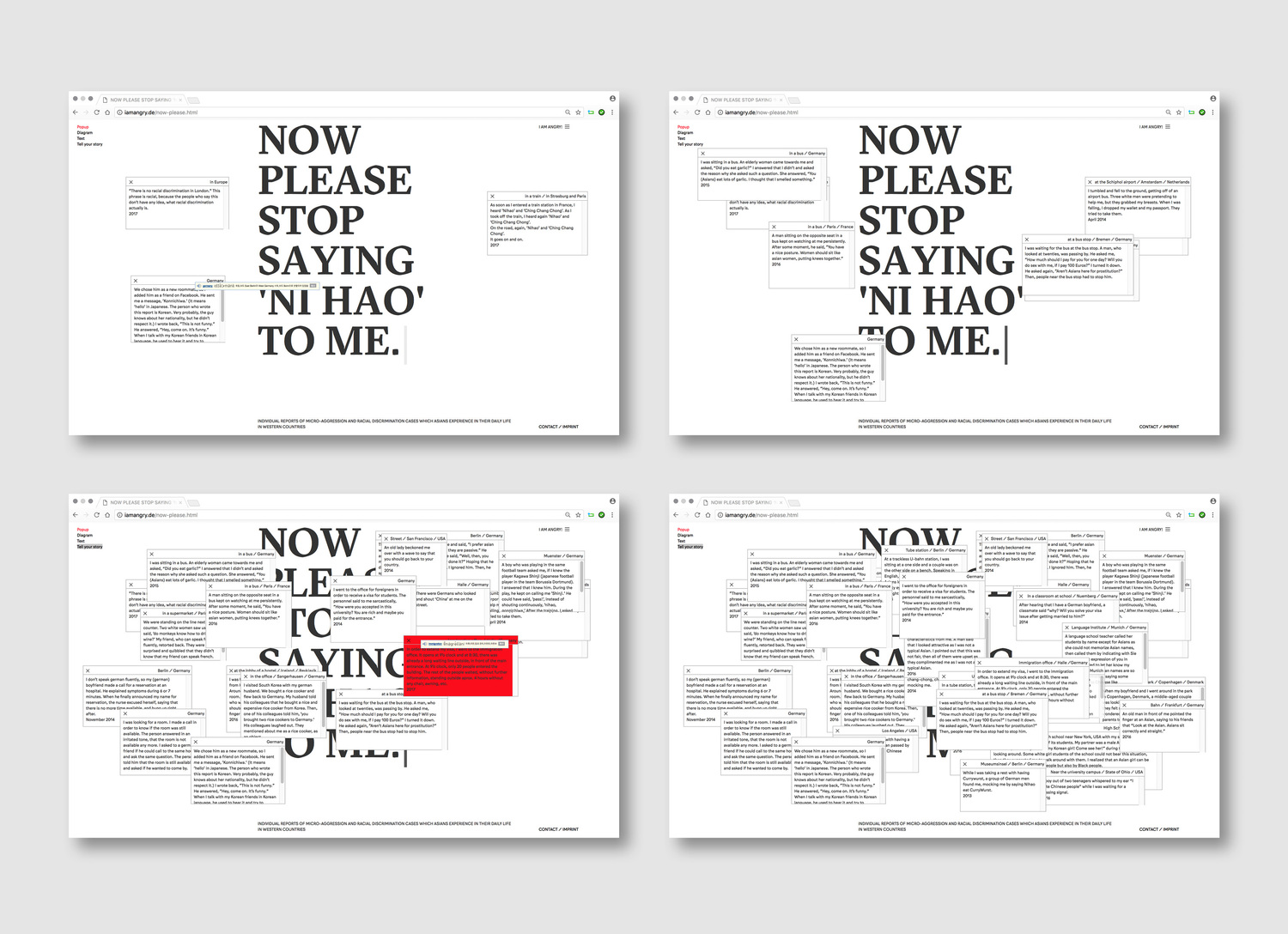

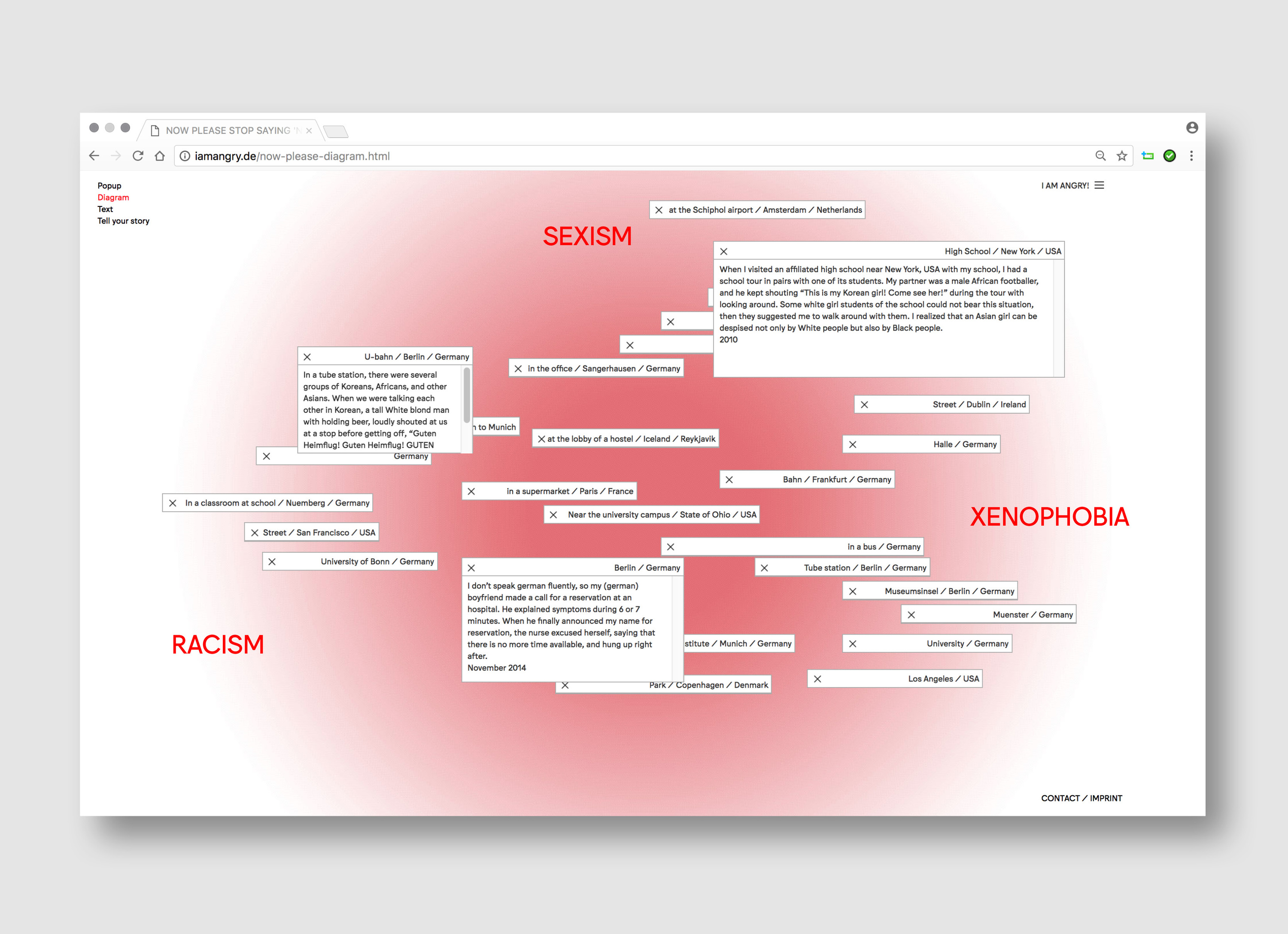

I am looking at Jihee Lee as my source of inspiration. Lee is a Hamburg based graphic designer from Seoul, South Korea. One of her works that made an impact on me is I Am Angry., (2016), which is a collaborative work between her and another designer, So Jin Park. I Am Angry. is a campaign that is based on microaggression, everyday racism, and discrimination against Asians. They came up with the idea for a platform where people with Asian heritage could share their experiences.

I think this is an excellent example of how designers can help contribute to society based on a specific problem. Lee as a designer had put the unsaid into words, turning an experience into a personal issue, making this personal issue into a common one, and bringing it into the public by inventing a platform where everyone can tell their stories, all while being very successful from a graphical viewpoint. I cannot disregard the fact that as human beings, we are attracted to visuals. Therefore, as designers, we have the capability to talk about and to shine a light on a particular topic; not necessarily to find a solution, but to try and make the world slightly a better place.

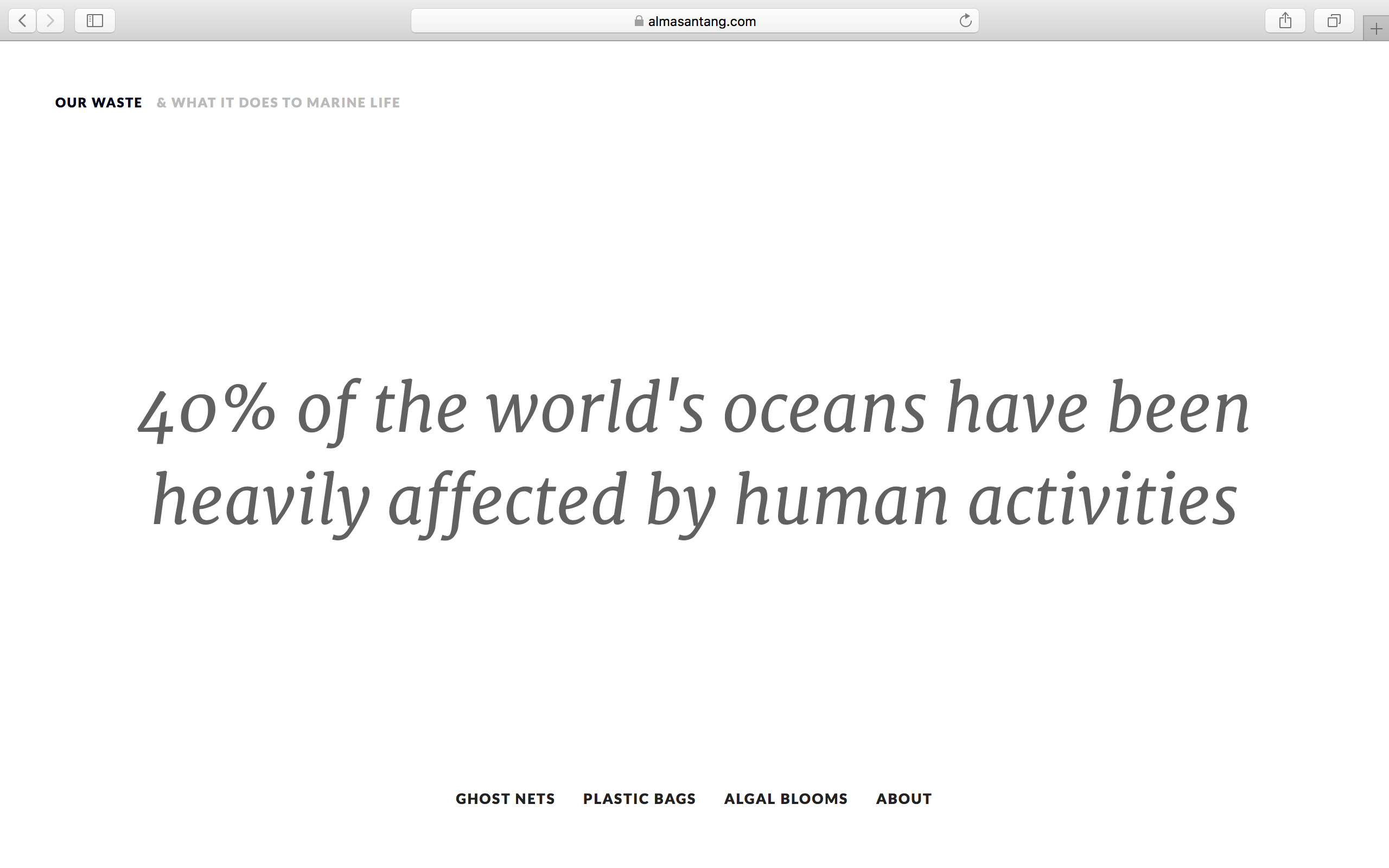

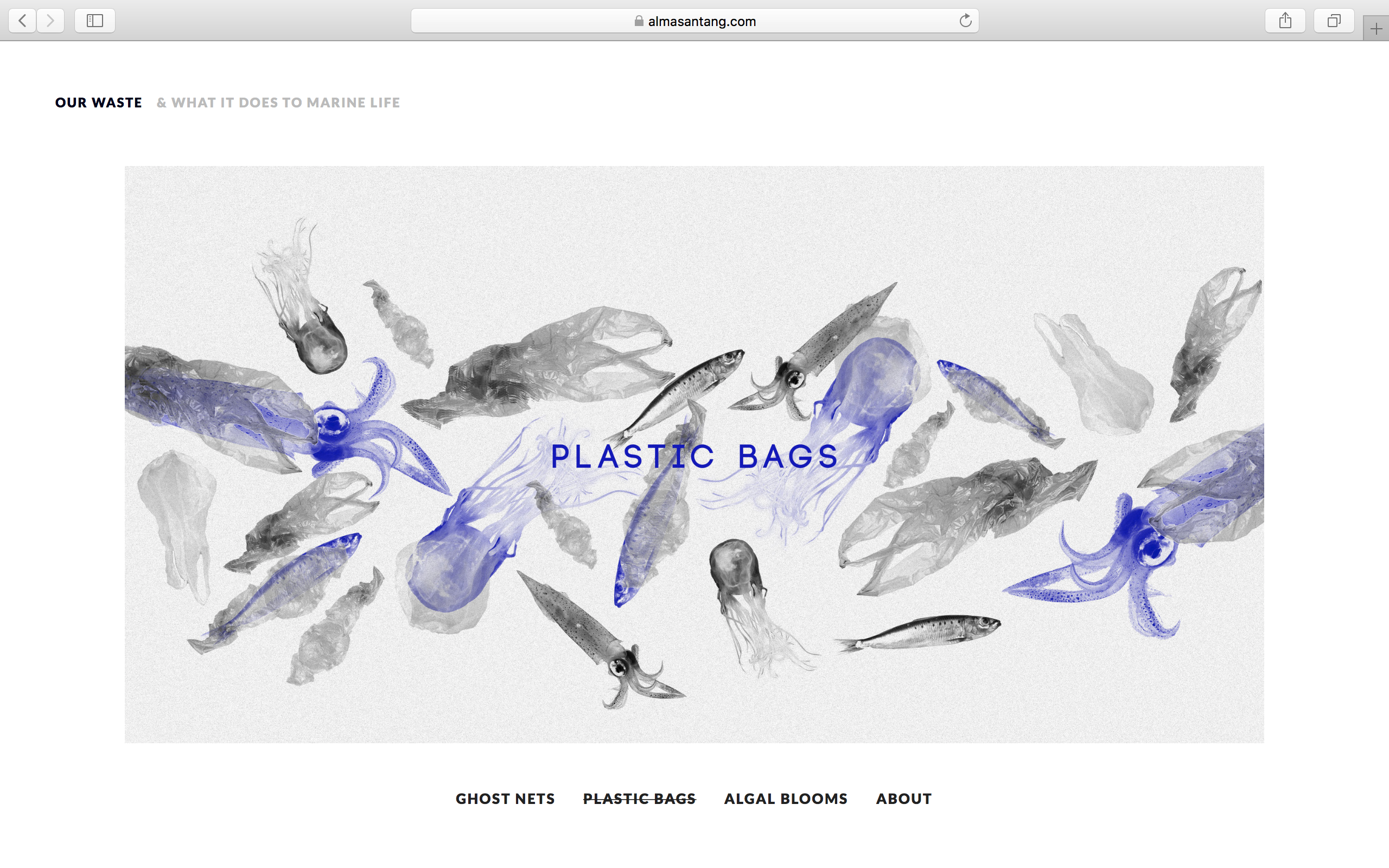

I personally resonate with the idea of social design as I tend to find myself drawn to social or environmental issues, which influenced my design practice. Our Waste is one of the projects I did which was based on an environmental issue. I created a platform which showcases how human activities disturb the ecosystem and putting marine life in danger. While this platform might not create a real-life impact like Lee’s I Am Angry., it might still put an effect on someone’s lifestyle (by trying to be more eco-friendly for instance).

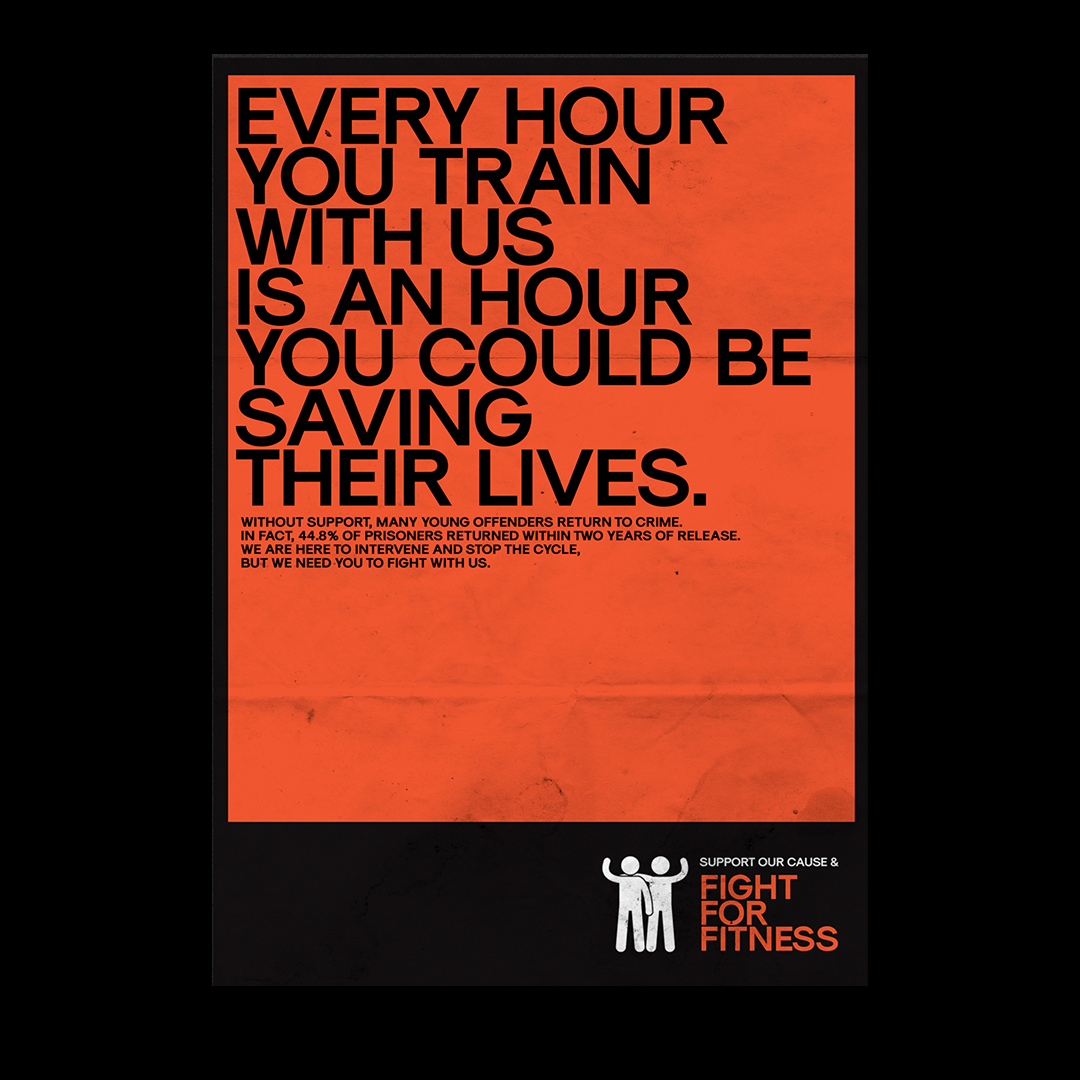

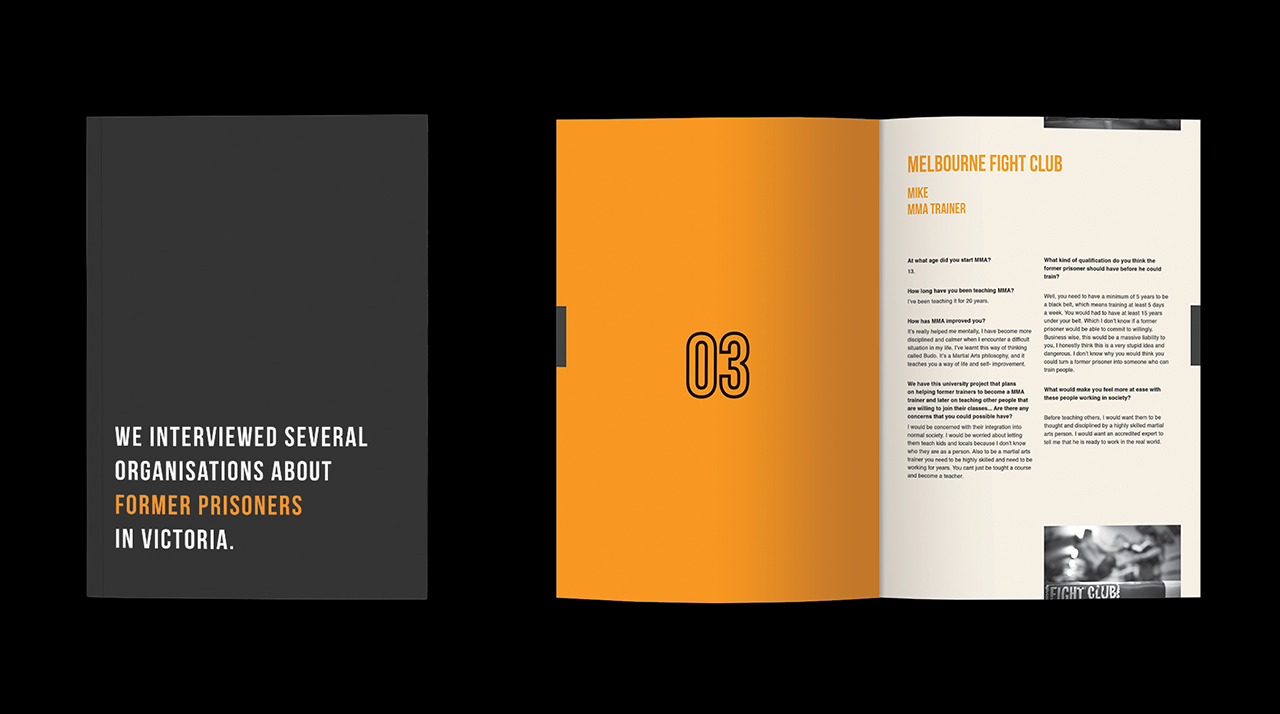

On another project that I did, I conducted research on former prisoners—focusing on their employability rates—by contacting several organisations in the field. The result from this 12-weeks long research was a proposed design solution, Fight for Fitness, a program to help reduce youth incarceration by utilising fitness. It is a personal training service that aims to close the gap between former prisoners and the community, by using fitness to replace segregation with opportunity and hope. The idea is that by completion of the program, the participants would be certified personal trainers. However, this type of non-profit design was not about the design outcome itself; it was about the people we were helping. It was not design for the sake of designing a solution; it was about designing for social good.

Andrew Shea, on Designing for Social Change, said that the process of helping communities often motivates designers to work on similar projects in the future. This ripple effect in the design community could place graphic designers in key positions across industries where they could make a positive impact. The idea of social design and the developing discourse around it forces me to rethink what design is and as a designer, I will continue to help create impact in society in any way I could; with a hope that the water will continue to ripple.

References:

Engholm, Ida. Salamon, Karen Lisa. “Design thinking between rationalism and romanticism: a historical overview of competing visions.” Artifact, Volume 4:1 (2017): E1.1-E1.18.

Christoforidou, Despina. Olander, Elin. Warell, Anders. “Good Taste vs Good Design: A Tug of War in the Light of Bling.” The Design Journal, Volume 15:2 (2012): 185-202.

Shea, Andrew. Designing for Social Change. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2012.

Brillembourg, Alfredo. Clarke, Alison. Fuad-Luke, Alastair. Julier, Guy. Margolin, Victor. Verbeek, Peter-Paul. Design for the Good Society: UM 2005-2015. Rotterdam: nai010, 2015.

Margolin, Victor. “Social Design: From Utopia to the Good Society.” In Design for the Good Society: UM 2005-2015, 28-42. Rotterdam: nai010, 2015.