The design world of the 21st century is a rapidly evolving one, especially when it comes to its impact on the earth. Sustainability in design is a value I that I have recently come to appreciate and understand, and I believe it is important to maintain an environmentally conscious mindset when approaching design.

The fashion label ABC.H World is a brand that strives for the most ethical outcomes and at the same time does not compromise for style. Not only are the fabrics they use sustainable, but the process in which they are made meet ethical standards and working conditions [1].

(A.BCH World)

Last year I participated in the Monash Prato study tour, where we were taken on excursions to various fabric production companies. I was able to grasp a better understanding of the origins of materials, the unethical working conditions in which some were made, the water wastage through dying and washing fabrics and the lack of transparency that many well known fashion labels fail to deliver. It also came to my attention that for a label to mention the usually glorified “Made in Italy”, only 20% of the physical item has to uphold this.

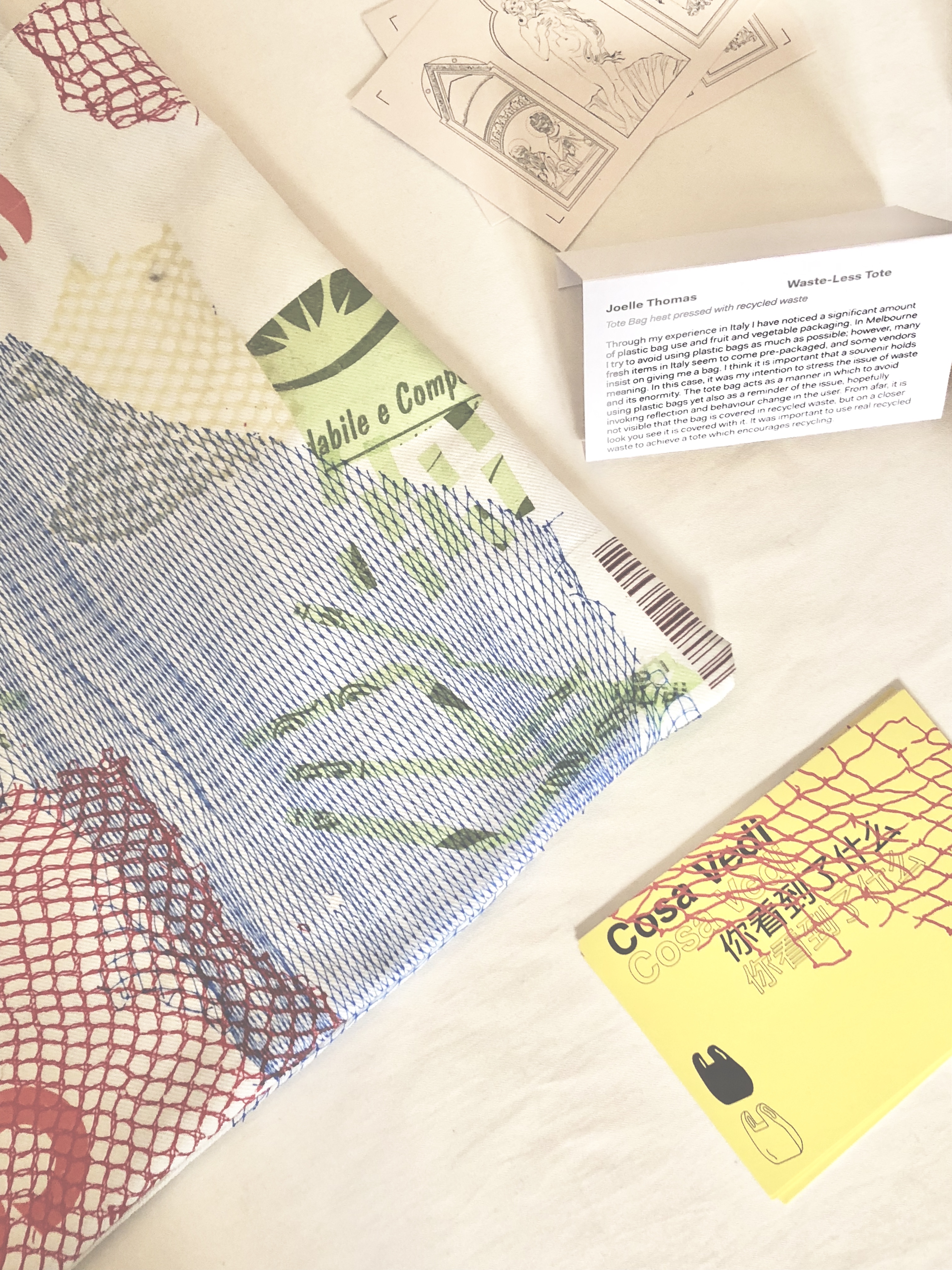

As a result, for my project during that stay, I decided to ensure an ethical process and outcome, from start to finish. The brief was to create an unconventional souvenir, something that went beyond the stereotypical fridge magnet or keyring, and spoke more of Italy and my experiences there. I had noticed the amounts of waste, especially at supermarkets. Packaging, plastic bags, and an excessive amount of receipts. Having had access to a heat press at the Lottozero, I created a tote bag sewn out of second hand material, and utilised the heat press to seal in various plastic waste such as shopping bags and fruit nets. As a result the bag acts as a substitute for single use bags and simultaneously speaking of the excessive amounts of unnecessary waste. I enjoyed creating something both practical and ethical.

Good Taste vs. Good Design discusses the connotations of ‘bling’ and whether the price value of bling can dictate it as ‘good design’ [2]. This makes me re-consider how big prestigious brands such as Louis Vuitton, Armani and Prada are labeled luxurious, yet fail to meet so many ethical standards. The fashion might be on trend, but at what cost? Can their clothing still be perceived as ‘good design’ if it is not made ethically?

I think it important to make a conscious effort, where possible, to shop and design ethically whilst also being weary of the lack of transparency some brands may have. For example the development of Whole Foods leads to seeing “the marketplace as a powerful but morally neutral vessel that can be used to promote good as well as bad” [3]. Its ethical intentions are good, yet it still manipulates buyers into mass consumerisms through idealised advertising.

Although I’m no fashion designer, I have found that through understanding the textile industry, and seeing successful brands such as A.BCH world I am now more determined to reflect this new knowledge into my communication design work. It has made me consider more the type of places I want to work for, and where I will need to draw the line between my values and my work.

[1] A.BCH World, Date accessed: 6 April 2019, https://abch.world/pages/about-a-bch

[2] Despina Christoforidou, Elin Olander, Anders Warell and Lisbeth Svengren Holm (2012), Good Taste vs. Good Design: A Tug of War in the Light of Bling. United Kingdom.

[3] Adam Mack (2012), The Politics of Good Taste Whole Foods Market and Sensory Design. United Kingdom.