By Sarah Toal

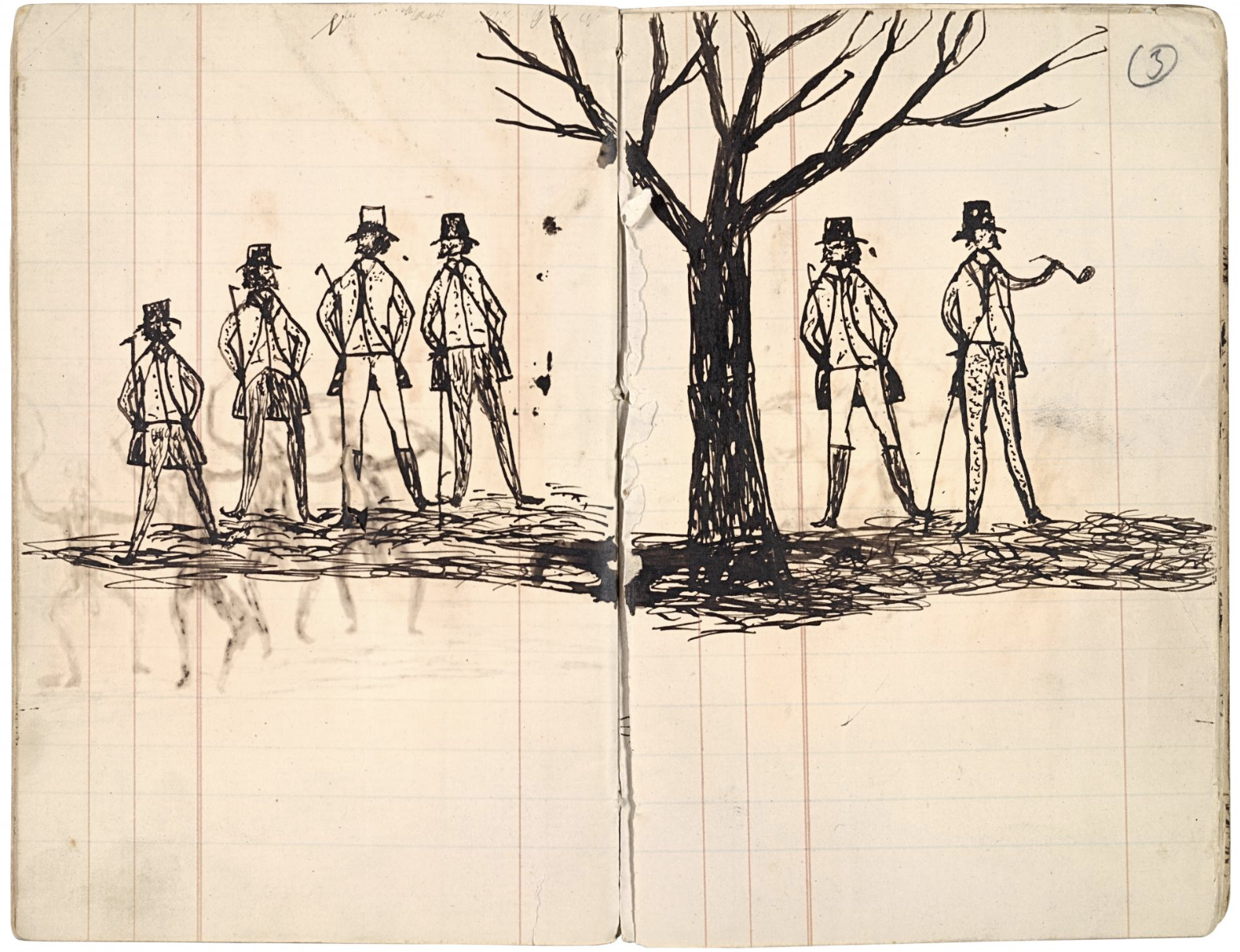

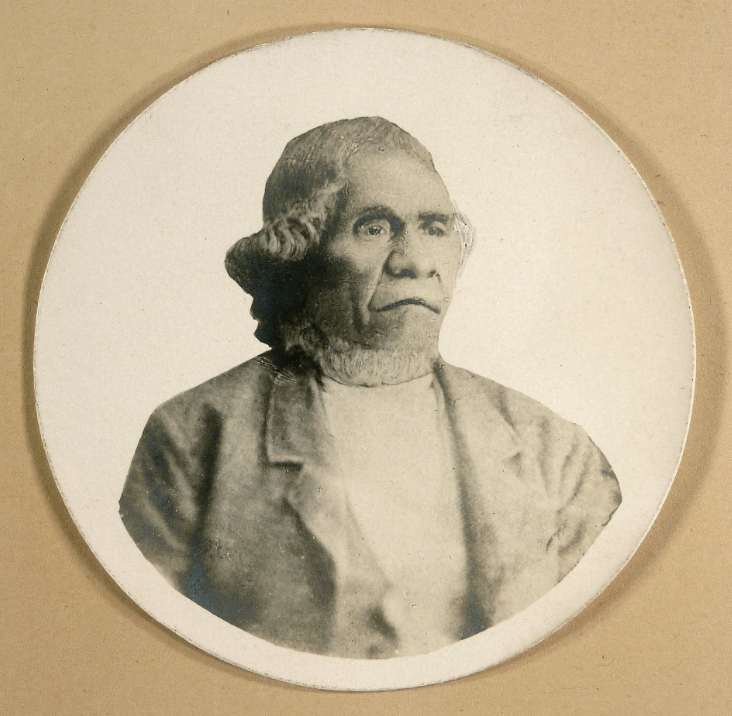

What does it mean to be a forgotten ‘superhero’ of design? Could it refer to someone who has fallen through the cracks of the design world? Or could it be a reference to Fry’s theory of marginality, that being, those ‘rendered silent’ by the ‘Eurocentric’, ‘dominant’ voices throughout history [1]? The piece presented here to explore this statement is by Tommy McRae, an Aboriginal artist from the nineteenth century [2]. He was presumed to be a Kwat Kwat man who drew his observations, outlining his perspectives of the events happening around him throughout the time he lived [3][4]. The piece in reference is titled “Squatters”, created using black ink on paper and is part of the extremely difficult to obtain, ‘Notebook’, 1875 [5]. This piece was acquired by the NGV, having been originally owned by McRae’s supporter Canadian Roderick Killborn, who commissioned drawings from McRae throughout the time he lived. ‘Squatters’ represents a ‘kind of narrative’ that only someone outside of Western culture can tell [6]. The figures represented in McRae’s designs can be a reference to the European settlers of the time, drawn hollow and less expressive in contrast to the other highly rendered figures featured within his work [7]. This use of storytelling through imagery provides an intimate and subjective view of Australia’s past, one that contrasts from Australia’s previously ‘eurocentrically grounded’ history [8].

It is important to consider Fry’s theory of marginality to analyse McRae as a designer and his work’s place within Australian history. According to Fry, artists like McRae fall under the marginal category of designers because they don’t fit in with Western ideologies or ideas of modernity. However, it is increasingly apparent that work like “Squatters” are important within the understanding of Australia’s history, and what forms Australia’s design history. Fry states that design history in Australia is made from ‘forces of import’, meaning we have had no individualised design history [9]. McRay is an example of how Australia has often forgotten the works of Aboriginal artists as part of design history. Australia’s design history lies within the voices of those who have been rendered silent, those who have fallen victim to ‘ethnocide’, that being ‘destruction of the culture of the “other”’, culture that doesn’t reside within ideals of western culture [10]. However, in recent times Australia has been more open in the exploration of indigenous culture, with artists such as Tommy McRae being increasingly celebrated. This is evident through more information being provided on indigenous artists, pieces such as “Squatters” being presented and charters such as the Indigenous Design Charter being created to allow for appropriate representation of Aboriginal culture [11]. Acknowledgement of Indigenous culture has allowed Australia to take a step forward in preventing the ‘covert, or even unconscious’ acts of segregation within design practice [12]. This begs the question, is Tommy McRae still a ‘forgotten superhero’ within the design world? Or is Australia on the right path towards more representation that will allow artists like McRae to be celebrated?

References:

[1] Tony Fry, “A Geography of Power: Design History and Marginality,” Design Issues 6, No. 1 (Autumn, 1989): 17.

[2] Nerissa Broben, “Tommy McRae,” Culture Victoria, accessed April 11 2019, https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/aboriginal-culture/the-koorie-heritage-trust-collections-and-history/tommy-mcrae/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jryan, “Tommy McRae’s Sketchbooks,” National Gallery of Victoria, accessed 11.04.2019. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/tommy-mcraes-sketchbooks-2/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Fry, 17.

[7] Jryan.

[8] Fry, 22.

[9] Ibid, 20.

[10] Ibid, 18.

[11] Russell Kennedy et. al. Australian Indigenous Design Charter – Communication Design (Australia: 2016), 1.

[12] Dimeji Onafuwa, “Allies and Coloniality: A Review of the Intersectional Perspectives on Design, Politics, and Power Symposium,” Design and Culture 10, no.1 (2018): 9.