MUMA’s current exhibition Shapes of Knowledge showcases eight artistic projects from Australia and the world, and by doing so, it invites the audience to think about the interrelationship between art and their own ways of knowing. Not only does the exhibition challenges the conventional knowledge of the public that concerns us in the present world, as discussed in my other blog “Fossil Fuels + the Arts?” it also brings up things that happened in the past.

One of its participants, Asia Art Archive, provides rich materials on how the activities of art institutions make great impacts on the history of art in Asian countries. There is one person, whose work and stories almost take up an entire section that was on display. His name is Zheng Shengtian – artist, designer and scholar who built the bridge between artists between China coming out of isolation, and the rest of the world.

China’s history of isolation, to some extent, can be traced back to the 1400s. However, the years between 1966-1976 were especially hard for Chinese people that lived in the 20th century. During the ten-year-long Cultural Revolution, China’s tertiary and higher education was completely suspended. Art practitioners like Zheng Shengtian were instructed to produce propaganda art for the state in Socialist Realism style – a genre of oil painting that portray an idealised lifestyle of the people. (Figure 1) All other forms of art were abolished, whether it was modernist or traditional. Art produced in this period were closely linked to politics, and the movement’s impact on Chinese art history was disastrous.

Today, the Cultural Revolution has become a phrase that the entire country would rather forget, and it is difficult to find an estimation on how many pieces of propaganda art were produced during the ten years. These art pieces float around Chinese internet mostly in the form of memes today. When people see these images, they would not even raise questions such as who created them and why were they created, but everybody would know that these artworks were painted for the state. The presence of the individual artists was greatly reduced. I cannot help but compare these artists to the collective art groups that emerged in Australia around the same era. Both the collective art groups in Australia and the anonymous propaganda artists in China were creating art to politicise people, even though one is radical and self-generated, the other one is state controlled and has no artistic freedom.

Of course, painting propaganda is not the reason I consider Zheng as a forgotten hero. What makes him a hero is what he did to help art “heal” in the post Cultural Revolution years.

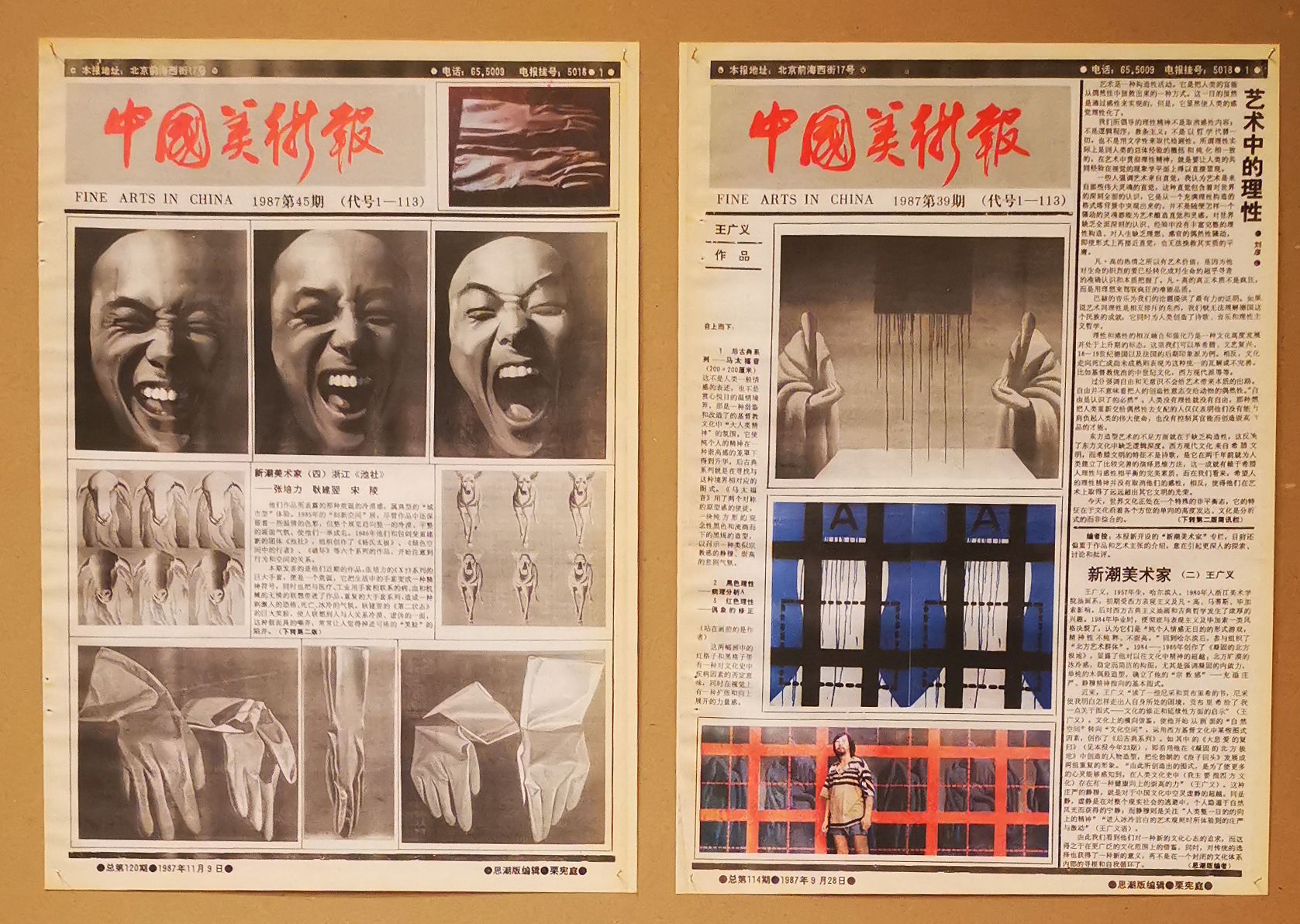

Zheng teached at one of the best art academies in China. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, he was the first ever artist that passed the English exam and was allowed to visit abroad. With the two cameras he had on him, Zheng took the opportunity to document every single artwork he saw while visiting international galleries, from New York to Vienna. What he brought back to China eventually, in 1983, was thousands of images of Western art to inspire and educate artists and the younger generations. He single-handedly opened a gate of communication between the Western art world and Chinese artists. Students in China at that time had the freedom to experiment and create – which led to the New Waves Movement of the 80s, where the very first group of contemporary artists emerged in China. (Figure 2)

Tianlan He (Tina)

References:

- Asian Art Archive, “Interview with Zheng Shengtian on Chinese contemporary art in the 1980s” (online video) , published March 2011, accessed April 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm2h_6HJ3uQ

- Jess Berry, Earthworks and Beyond (2010),https://lms.monash.edu/pluginfile.php/8323623/mod_resource/content/2/earthworks%20book%20chapter.pdf

- Monash University, “MADA Art Forum: Asia Art Archive: Art Schools from Asia,” Monash University Museum of Art, accessed April 2019, https://www.monash.edu/muma/events/2019/MADA-Art-Forum-Asia-Art-Archive-Art-Schools-from-Asia-Part-2-ChinaIndia

- Monash University, “Asia Art Archive: Art Schools from Asia: Three Case Studies,” Monash University Museum of Art, accessed April 2019, https://www.monash.edu/muma/exhibitions/exhibition-archive/2019/Shapes-of-knowledge/asia-art-archive