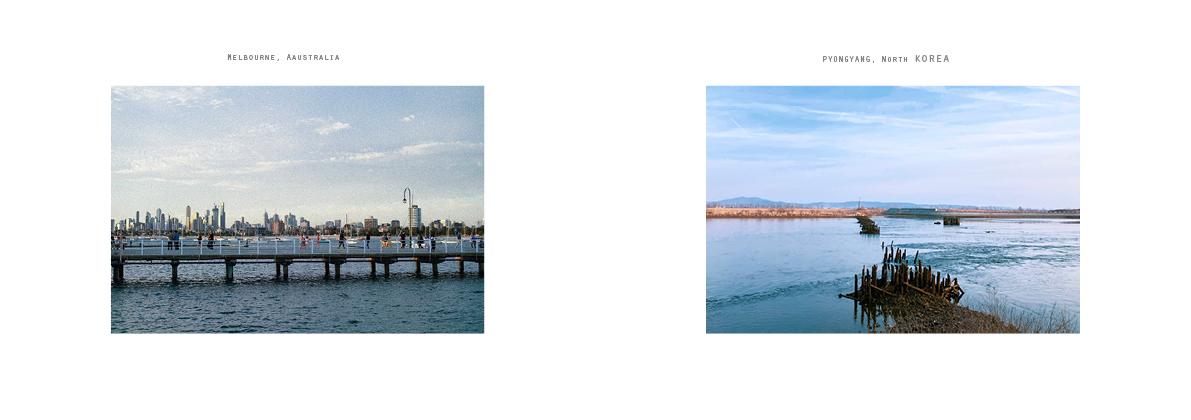

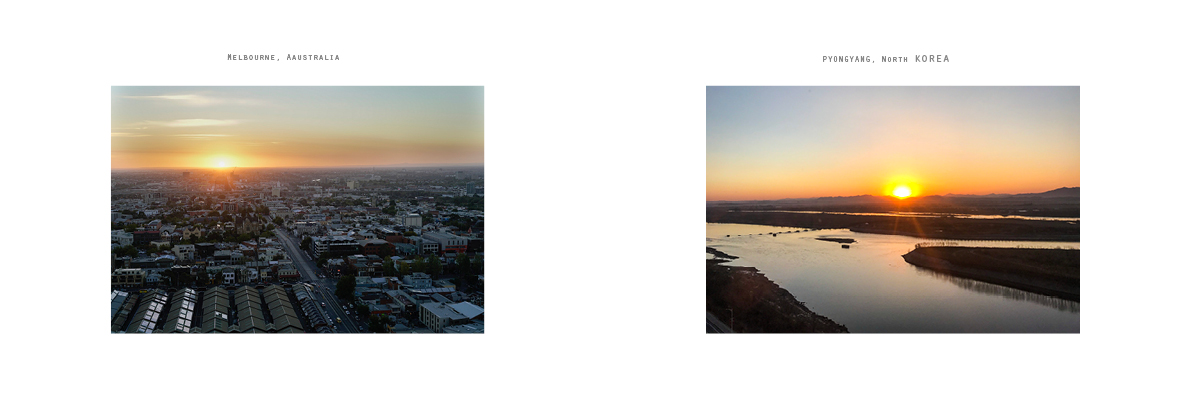

“the more of less” is a publication featuring a series of landscapes of Pyongyang the capital city of North Korea and Melbourne. Both Pyongyang and Melbourne are the most bustling city in their country. This photobook draws inspiration from the book ” [1]. The book conveys the message that there is more to be had in owning less. Joshua Becker also establishes his own “simplify life” rules through sharing different people’s life experiences and stories. To further develop the idea “the more of less” from the book. I transformed the text into a visual art form which offers more direct experience to people, allowing them to gain quick ideas of minimalism. This photobook is not just a book with splendid imagery but a simplify easy-read version of the textbook.

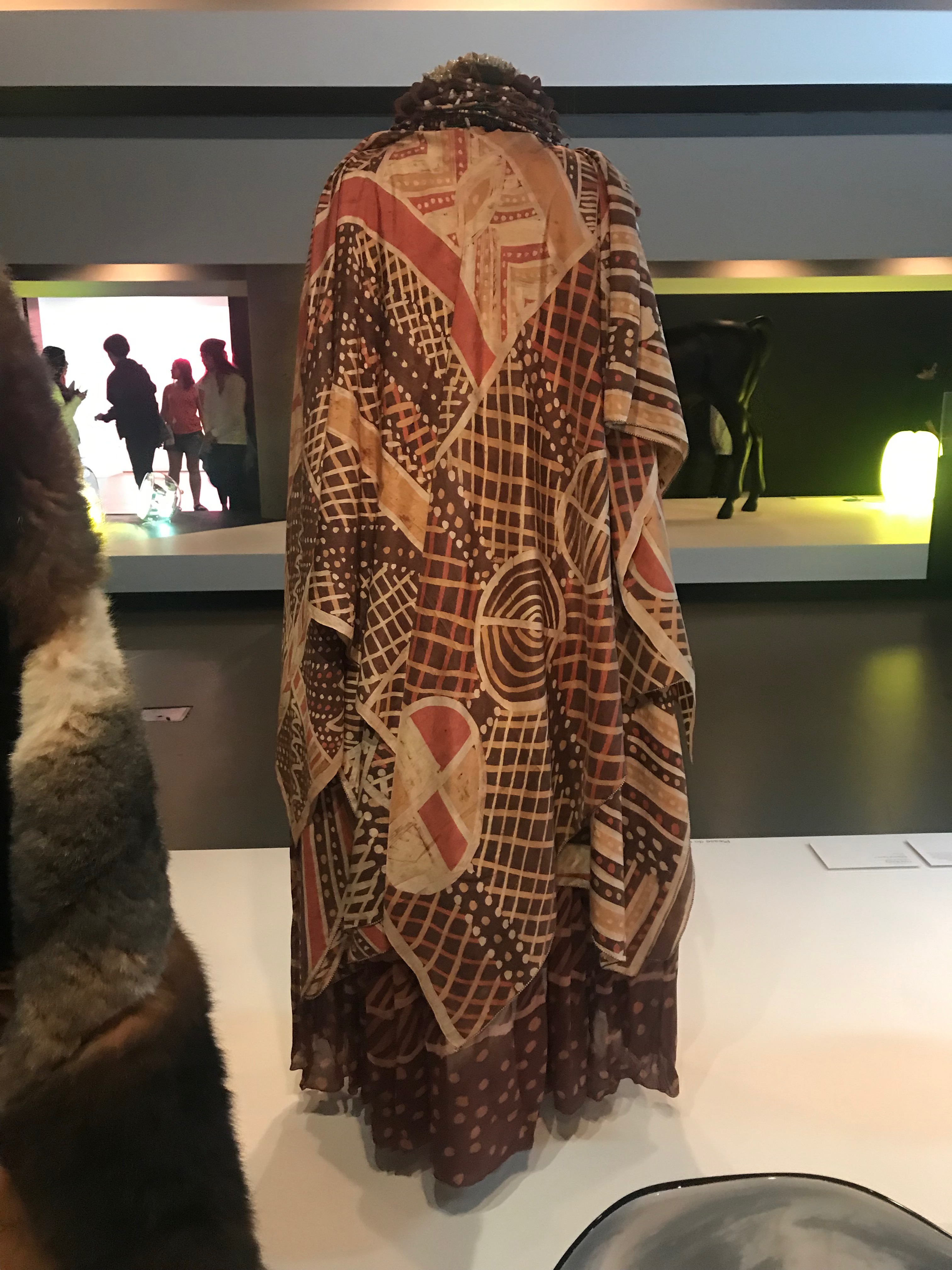

For a long period of time, North Korea has been described as weird, a dictatorship of the most extreme kind[2], however, I would like to provide a different perspective of North Korea in a design aesthetic way. Rather than its underdeveloped and closed-off, I found this place somehow matches the idea of minimalism. 1. Simple and minimal design elements: a lot of white space on the wall due to no advertisement. 2. The use of restraint: restrict color palette of all buildings as well as limiting content on everything. 3. One single standout element: all propaganda that you can see is mainly focused on the leaders and their greatness.

In order to better emphasize Pyongyang city’s minimalism, I have a look into Dianna Wells photograph work “On Edge” [3] which explores the transition and tension between the old pastoral and the new expanding urban landscape in Melbourne City. In her pictures shows the “tension point” between a suburb and nature view, which to tell people how a city has lost contact with nature gradually, she strongly features out the future of Melbourne’s fringe that is just about to happen.

Like Dianna Wells’, I have involved critical design thinking throughout my work according to the article “Critical design as approach to next thinking.” [4]I used Melbourne urban footages as a comparison group to stand out Pyongyang’s natural environment. The emphasize focus on a future living situation: from Pyongyang city to Melbourne indicated the evolution of a suburbs development with future. My photographic works have expanded the social meaning of a clash between an urban living city and an underdeveloped but yet have a more natural environment country. which makes people consider their future and their own impacts on the environment as potential decision makers, questioning themselves what will be like in the future for a city that its natural landscapes are rapidly turning into urban development?

In conclusion, “the more of less” is trying to make people concerns about future space and living through critical thinking, by comparing Pyongyang’s natural landscapes and Melbourne city urban life. The work also drops a hint that Pyongyang would likely develop into Melbourne which lets people realize how our choices in the present could influence the future. Therefore I have urges that minimalism lifestyle would bring a more environmentally friendly future rather than excess production and consumption.

[1] Becker, Joshua. More Of Less Finding the Life you Want. America: Waterbrook Pr, 2018.

[2] Jakobsone, Liene. “Critical design as approach to next thinking.” The Design Journal, 2017: 20.

[3] Jordan, Caroline. DIANNA WELLS. 8 September 2012.

https://www.diannawells.com.au/new-blog/2019/3/25/on-edge-caroline-jordan.

[4] North Korea country profile. June 13, 2018.